Now Reading: “के गर्ने ?” Contemporary Times in Nepal: People, Cultures and Architectures

-

01

“के गर्ने ?” Contemporary Times in Nepal: People, Cultures and Architectures

“के गर्ने ?” Contemporary Times in Nepal: People, Cultures and Architectures

Nepal is a fast changing nation. ‘ke Garne?” – the traditional idiom of acquiescence ‘What to do?’ is becoming a request for action. What was un-dreamable only a few decades ago has become an everyday reality for the Nepalese. This paper traces the changes of Nepal through the writer’s first- hand experience in the country for over 30 years, tells about the nature of people and opportunities today ,and describes current ideas and projects which are now being developed with partners in Nepal.

I was left alone, imprisoned by circumstances on the deck of the rusty old boat between India and Sri-Lanka. It was a magical night on an ocean dotted with reflections of stars on the silvery black ripples. The police officers slammed the gates of the country shut without letting me in. I did not have the visa I needed in my Israeli passport, and could not return to India with my expired single entry: “…do not be upset”, the border police officers said politely, comforting that “it is not personal, it is between our countries” when they saw me worried.

But personal it was when I reached Nepal, rushing with an emergency three days’ visa through India after non-stop day and night travel on the hard wooden benches of the second class trains, in the stale air of cheap oily ‘fooding’ and sweet tea, crammed with millions around me, who insisted to hear about my distant world – about the name of my father, my mother, my husband, brothers and uncles, how old they all are, what do they do for living, how much they earn, what do they eat during the day, how many children they have, and many such details about the rest of the world – perhaps disappointed that it is not so different from theirs. I was sitting on the benches just waiting for those extremely long three days to end. An orange sunset welcomed me in as I crossed the northern border with my old back pack, when a petit man in khaki and red uniform smiled at me at the border station. I was distressed with “…what is wrong now? how many rupees will he demand for ‘bakshish’ ? what will he want now? …”. I was almost paralyzed with worries as he nodded his head left to right and went on with his job till I heard the thump of the seal stamping the visa onto my passport and handed back to me with the same bright eyes and big smile wishing me a good time in Nepal. Only then it hit me that perhaps he is nice to me because he is nice. This smile dissolved my worries and my heart could open again to see and explore the country I entered for the first time. It was a special entry – with long shadows and misty blue hills under the orange skies accentuated by the bright eyed smiles of the curious officer who watched me closely. I had just entered Nepal and could not know that this was the beginning of a life-long trip and the foundation for my very long relationship with the country for the decades to come.

I have mostly learnt from Nepal It opened my mind to see the beauty of humanity – that differences are the wealth of cultures, and that they dissolve when humaneness comes to the fore. I learnt how cultural constructs are so embedded in the environment, and how they evolve through time and social locality, and how humanity can transcend constraints through community wisdom and shared efforts. I was amazed to see how possible is the impossible, and the incomprehensible makes so much sense: I saw the most delightful war.

It was a real war between east and central Nepal that I witnessed in a remote village in north Nepal – a place which, at that distant past some 30 years ago, was linked to the worlds outside the hidden valley by a single narrow, recently opened path that crossed ridges and high mountains. There were no roads, no cars, no telephones, no electricity and no running water – it was still a world enclosed with snow-capped high mountain walls in black granite, in almost complete isolation. I had just come there with a group of porters from Eastern Nepal who brought my equipment for my ‘fieldwork research’ I set out to do for the PhD I had just begun. We all sat around the fire after the dinner we shared with the villagers.

As we finished the salty tea and went on to the Raksi (local hard alcohol) the hosts and visitors discussed and compared their worlds, weaving some songs into the lively conversation. It was fun till a point when suddenly their voices grew louder with a hidden animosity that sparked fire into the gentle debate. The two groups of men grew apart, and the discussion heated: whose rice is better – theirs, of the lower lands in East Nepal, or the rice of the high lands in Central Nepal?. Between argument and competition – it was a fight about the grain of rice, the size, ease of harvesting, husking, threshing and winnowing, and surely, cooking it, the taste of food and, of course, of the women who cooked it. Then it evolved into almost war about farming, traditional rituals and songs, and songs in general. Then, as the Raksi was settling in, the competition grew fierce, and dances were added to prove the point. The thumps shook the floor and the sounds became louder till late, until the fire turned into embers, the Raksi emptied out and the energies drained, till one after the other the men went, or dropped into the corners of the room, muttering some words of praise or of anger and vanished into deep sleep. When the sun rose as early as it always does the next morning, people parted with assured smiles – the villagers went to work in the fields, the visitors went back home in the east, all feeling that they won that war – everyone was reassured that his rice is better, his songs and dances are better, his language is richer and his home is the best.

Today’s Nepal is very different

It is a republic of fast changes, accelerating urbanization, where openness and education have transformed it to a land of possibilities. Nepal today is un-comparable to its past of discrete communities, each with their own language, economy and lifestyle, controlled by a disaggregating regime. Since the demise of the monarchy, the decade of insurgency which followed, and after the tough beginning of the new era where people were fighting on the streets of cities and in mountain villages to define their democracy, today, the recent division into provinces that had fragmented the dysfunctional centralization seem to have found the appropriate scale for the nation, perhaps more familiar to a people with a long history of tiered Panchayat councils. Nepal today is a liberal democratic republic with political stability and cooperating coalition politics.

The people of Nepal today are completely different. Mobile phones are everywhere, even in the most remote villages. Computers are common knowledge even where they are inaccessible, communication networks, radio, TV and the internet, have brought the world to the remote people of Nepal, and the new roads have shattered the barriers of distance. The cities are bustling with cars and motorbikes as the young entrepreneurs are immersed in the screens of their smart-phones, latest models, setting up a new project or arranging the next deal.

The enormous difference between the young Nepali adults and their parents’ generation cannot be underestimated, particularly in the towns and cities of Nepal which are growing at an overwhelmingly accelerating pace. It is a generation which was born into democracy and struggled for the emerging liberalism, educated people who grew in a Nepal of open borders and fast communication, in the modest homes of the evolving middle classes, where free economy and private enterprise has become the ideal and the challenge. This, together with the creative mindset that was born from the necessities of poverty in Nepal’s ‘previous life’, of traditions, joint-family and close social groups, makes the young adults of Nepal a unique group of able, educated people who are eager to take on the new challenges of the 21st century despite the scarcity of means at hand.

It is this generation that is shifting the meaning of the most common idioms of Ke garne? . ‘What to do?’ epitomized the Hindu-Buddhist traditions in Nepal denoting the historical stance of acquiescence, acceptance and passivity to a certain extent: ‘Sansaar yestai chha’ – life is like this” they say. Today ‘ke garne’ is being asked in an active mode – towards taking steps of action for change, taking on challenges – a dynamic stance of taking action to make a difference.

Nevertheless, while GDP and GNP are growing, and personal income increasing even in the more remote villages – poverty – merely a comparative concept, not a condition to be measured by US$ income per capita – has increased. Communication has brought home absences and created poverty, yet, at the same time it is also shaping the new challenges and drive for change which characterizes the shift of Nepal towards its dynamic life today. Having grown alongside Nepal and followed the way it has evolved, my own relationship with the country has changed. In the past I refused to join foreign investors or aided projects as I cherished the local worlds which were self-sustaining and content, and I felt strongly that ‘development projects’ were patronizing, or judgmental at best, resulting in using up resources where wealth is extracted and the balanced sustainability derailed.

My first accidental visit in the 1980’s, after that night on the old Indian boat on the silver ripples of the Sri Lankan ocean, has been most rewarding for me. Contrary to the well meaning border policemen, my travels to Nepal have become personal affair which has changed my life. I feel privileged to have many friends from all walks of life – people of the aristocracy of Kathmandu and the poorest of the Dalit in far western Nepal; I know state politicians and local leaders, urban professionals, lower-middle class craftspeople, farmers in remote villages and Buddhist priests in isolated monasteries of the high mountains. I have known them for years and we travelled pieces of our lives together. We shared boiled potatoes and ‘lagar’ (mountain buckwheat bread), happiness and troubles, and we brought new insights to each other’s lives -I feel most fortunate for knowing them, and knowing Nepal so intimately through them.

It is for them, and for the fast shift in Nepal today that I have begun to engage in several initiatives in Nepal. This I do with my colleague and friend, Yoram Ilan Lipovsky under the umbrella of IAT – Ilan Advanced Technologies, partnering Nepali and Israeli entrepreneurs of vision and ideas, working together to strengthen weaker links or add a missing link by initiating projects which cater for Nepal’s contemporary needs. The guiding concept is that knowledge is shared, development and adaptation is done together in Nepal, mostly by the Nepali and for themselves, and profits are shared between us as partners, with a certain percent allocated for humanitarian work in Nepal to acknowledge our special relationship with Nepal.

But while most of these projects are based in appropriating advanced technologies to the unique conditions and particular needs in Nepal, the first and most important of these is our initiative is to preserve and promote the diversity of cultures by the creation of The Center for Cultural Excellence of Nepal, which we feel is the most urgent and pressing initiative, as I shall expand below.

Under the pressure of time

Nepal is transforming at an ever growing rate in recent decades – fast urbanization, economic emigration of laborers and professionals, and the growing consumption of cheap products and ready-mades have resulted in the fragmentation of communities and dissolution of traditions. At the same time that new employment opportunities help integrate the more remote villages into the Nepali economy, they detach the locals from the historical seasonal programs which balanced the traditional division of time between agriculture, manufacture and social and religious production. In practice, this means complete transformation of lifestyle, and loss of local knowledge, histories, crafts and languages: the cultural richness and self sufficiency are taken over by monetized economy.

This is neither good nor bad – as a common Nepali proverb explains: ‘Sansaar yestai chha’ (Np.: ‘life is like this’). It is what it is – like the weather, as I learnt from a close Nepali friend long ago, when he asked me, somewhat shyly, to explain a perplexing puzzle he could not resolve about us, ‘bideshi’s (foreigners). He asked why we say ‘good weather’ or ‘bad weather’ – and continued to explain his bewilderment when I raised an eyebrow: ‘after all, weather is weather’….

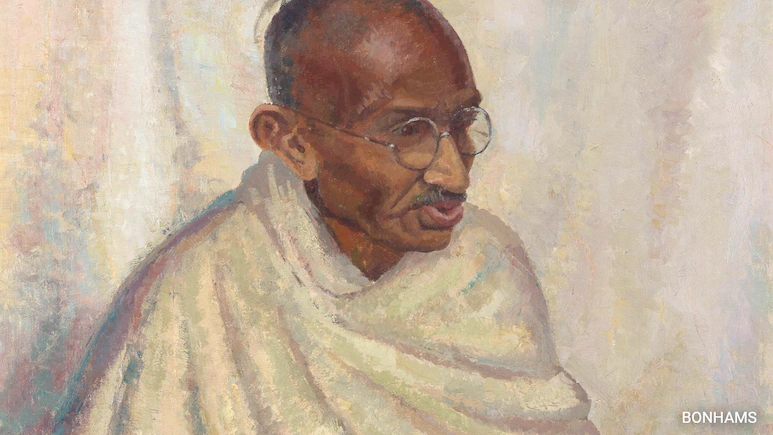

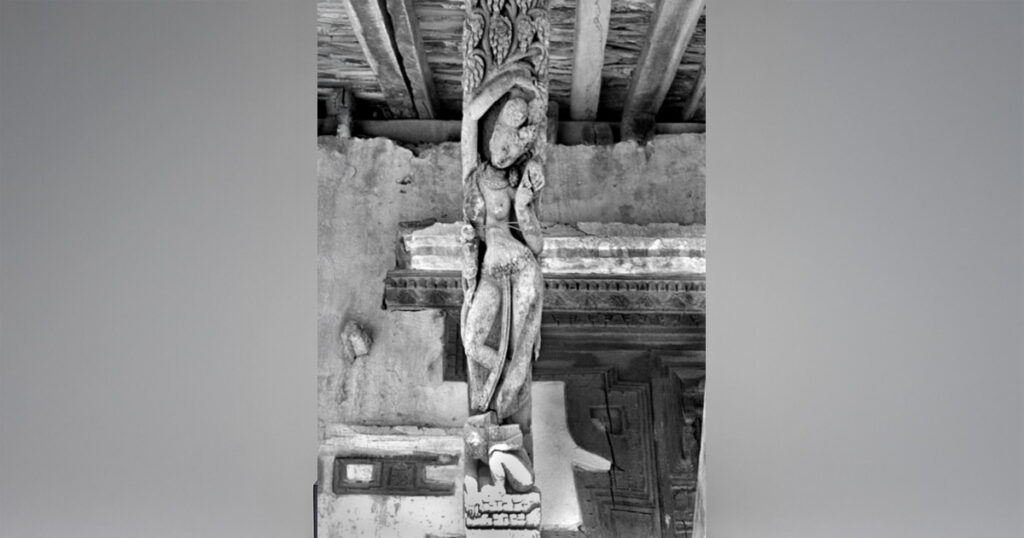

What has been unique in Nepal until recently is that artistic production, whether painting, sculpture, dance or music, has been inseparable from everyday life of the people, and has found its place in the crafts of pottery, brass casting, stone and woodcarving, architecture and decoration, ritual objects, jewelry, textile etc. as well as folk or religious music, dance and theatre. In contradistinction to the European traditions, where the production of the arts was patronized and produced for consumption by aristocratic courts or the churches, and the artist is a cultural hero, in Nepal it has been produced by the people and belongs to their everyday life. The artist is everyone, artistry is everywhere, and art is there to serve and to be used.

There is more in the loss of diversity. “There are only 56 languages in Nepal” once a German linguist explained to me, and emphasized : “languages, not dialects”. There were more, as I learnt from my Dalit friends in Humla during a three days’ ritual of dispelling a prophesy of misfortune to the life of a young man. There were dances around the fire through those freezing cold nights of November, when the men were singing the whole of the Mahabharatha. It was not Hindi, nor Nepali, nor any local language I ever heard of . They said it is in the original Khas language of west Nepal, that they did not necessarily understand – but they knew the words to sing together. This is still there – but disappearing. Today, the children of my Manangi friends do not speak their mother tongue, and the Nepali of my friends in Kathmandu is better than their English, they say.

The vanishing of this rich cultural diversity and the disappearance of the traditional arts and crafts in Nepal is a great loss – not only for the Nepalese, but for the heritage of the world just as much. It is only obvious that cultural discourse of people, environments and social practices is embedded in their cultural products and enhances their formal and aesthetic value as they reflect the social and historical processes which have produced them. The unique situation of Nepal – it geographical fragmentation, and relative isolation till recent decades, particularly of the more remote districts, have prolonged the historical ways of life and preserved its tangible and intangible cultural products, which have made Nepal particularly unique. In contemporary Nepal, this is now under threat of disappearing, and the sense of urgency is pressing.

Turning a problem into an opportunity has been my mother’s lifelong and indissoluble frame of mind – a holocaust survivor who refused to surrender to trauma or difficulties. It proves relevant here too: at the same time that contemporary life takes the traditions off the main streets of culture, this can now be studied, framed, and put on display to remember, study and promote. Todate, Nepal has had no institutions nor frameworks for doing so. There is a handful of the museums in Kathmandu valley do display some wonderful objects under layers of urban dust. Until recently, such efforts have fossilized everyday culture or architecture which was alive everywhere outside those institutions, and hence the disappointment of the visitors, local and tourists alike. Until recently, it would have been absurd to display the trivia of everyday life on museum pedestals. But now things have changed.

Center for cultural diversity

Turning a problem into an opportunity has given rise to our vision of regeneration. More specifically – the creation of a new home for Nepali cultural life of past and present – a place to preserve, study and debate and create everything, directly or indirectly related – a true center dedicated to the Nepali arts and crafts, to archive and display, a place for study and enjoyment of historical and contemporary paintings and sculptures, photographs and documentary, the artistry of architecture, of brass casting, of blacksmiths’ and silversmiths’ works, jewelry and textile, stone and woodwork, costumes and even cookery. It will become the center for the performing arts – of singing and music, of dance and theater. Education is to have a pivotal importance to the activities of the Center: beside classroom and workshop for children and adults to study and gain first-hand experience in the arts and crafts, it will be a place where local knowledge can be transmitted – alive and real. Furthermore, the historical collections will be but a part of the new digital library, equipped with the most advanced technologies to link it to the world’s best libraries, where access will be free and open to all, giving everyone an opportunity to develop. Such a place will become the new home to celebrate Nepal’s rich diversity and enjoy its differences when bringing in visiting exhibitions, performances and scholars. A place such as we envisage will become a central hub for cultural life in Nepal today – a link between historical traditions and contemporary discourse, which engages Nepali and bideshis alike, a place for cultural preservation and regeneration – a contemporary link between Nepal’s past and its future.

The creation of a national treasury of Nepal’s cultural history is our most important project initiative, where the collection will serve as a national cultural anchor for the country and serve as a reference point of identity to communities and individuals, and preserve peoples’ histories.

Regeneration: urban, cultural and economic vision of an architect

At this historical juncture architecture and urbanism can provide an adequate response and a vision for what is an urgent national necessity. Like temples or churches, the greatest of the world’s museums are important secular shrines to celebrate humanity’s cultural wealth. Such museums are mostly located in city centers and provide a magnet for visitors, locals and tourists alike, and become a magnet for many related social, cultural, commercial and educational activities which give the area around them a special identity in the urban context.

The vision for the new Center for Cultural Excellence of Nepal is free from the history-burdened centers of cultural repositories as in Europe and the US. It will be a new type of multi-functional complex which, in the context of Nepal, it will be a reflection of the country – almost an oxymoron – a place for the arts and crafts of Bahal’s (residential courtyards) and palaces brought together, for creativity of people in villages and cities, a reflection of urban and rural life, where ‘high’ and ‘low’ traditions merge and blend: a place to celebrate differences and enjoy the diversity of Nepal.

Furthermore, in practice, as we see it, regeneration is a process in the ways in which this long term project is developed – a process of partnering, sharing knowledge, learning, training and working together on the conservation and adaptation of historical architecture and new technologies, to create a facility that can make the knowledge of Nepali culture accessible to all. Such a project will create a new center in Nepal for its cultures to be preserved, remembered and referenced to, and perhaps transformed and made relevant to contemporary life, perhaps in a different form.

This project is designed to be economically sustainable in the long run. It was initiated by friends from inside and outside Nepal with whom we share our love and admiration for the vanishing traditions of Nepal. To-date this vision is well received and shared by many, and we pray that these new insights will prevent commercial market pressures or economic forces from thwarting our efforts to making this happen.

Besides, separately, and in addition to this – our intimate knowledge of Nepal, our in-depth involvement with the advanced technologies in Israel, together with our intention of working together in full partnership, has given rise to several new initiatives, where we plan to share Israeli and Nepali knowledge, learn, develop and train people in the process of implementation. Some of our initiatives are briefly outlined below :

STEAM – We believe that education is the foundation for the future so that every child has the right to fulfill his/hers potential and realize their dream. In the world of the 21st Century, the STEAM subjects – Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Mathematics – are the basis for contemporary life and development. This, plus the Plus framework we devised, where we designed a program to support the personal growth of the students, as individuals and as a social beings, and work to develop their social skills. The integrative approach of the program is an imperative in this century, where the screens are taking over unmediated contacts even among the younger of children.

RMI – No other country in the world is as fragmented by mighty mountains and deep river valleys which have made many of its parts inaccessible, hindered development, and prevented many from receiving good medical care they equally deserve. Our Remote Medicine Initiative (RMI), where advanced communication can bring medical care to distant places where there are no sufficiently experienced specialists, or no doctors at all. Together with one of the ten best hospitals in the world, Sheeba Hospital in Israel, we are working to make medical knowledge and experience accessible to even the more distant clinics and hospitals in remote parts of Nepal, guide treatment, relieve much pain and save many lives.

DMI – Our Disaster Management Initiative, brings together all the authorities and government instruments that operate when major disaster strikes (like earthquakes, landslides, fires, accidents, etc.), by identifying specific local needs, developing facilities and networks in order to bring the facilities of the center closer to the remote districts and reach in time. Strengthening the links between central and provincial governments will enable timely rescue and provision of supporting services to save lives.

One concept to varied projects –

There are several initiatives we are working to develop and share with Nepal – like the advanced technology earthquake warning system, air-lifted mobile hospital unit, and others. ONE CONCEPT unifies what is seemingly disparate , but not dissimilar projects, which, in our view, are founded on common grounds. All these initiatives begin with our intimate knowledge of Nepal on the one hand, and our long history of working together closely with the most advanced technological industries in Israel, in the academies, in practice, and in education, on the other. In bringing these together, tailoring them to the needs of Nepal, and sharing this with Nepali partners – we believe that our joint efforts and working together will be equally beneficial for all, and contribute to make the relationship between Israel and Nepal closer. Amen.

———– ————- ————- ————

This insightful guest article has been graciously shared from the esteemed book ‘Nepal Israel Relations- Dynamism of cooperation oppertunities, connections and actions’, with the hope that you find it enriching and valuable.

Written by Ada Gansach